One of the things that we’ve learned about Archbishop Justin Welby in recent weeks is that he gets upset about what people write about him on social media.

He wrote at some length about how what gets written online is upsetting and he’d just prefer to have personal contact with him rather than sounding off online.

Love often says don’t tweet. Love often says don’t write. Love often says if you must rebuke, then do so in person and with touch – with an arm around the shoulder and tears in your eyes that can be seen by the person being rebuked.

It is difficult not to have some sympathy for him and I say that as someone who has been really particularly critical of him in the past. It can’t have been much fun seeing my You Condemn It, Archbishop post being relentlessly copied, commented on and retweeted across the Anglican globe.

And yet the trouble is, there’s no turning the social media clock back. Wanting a world where people don’t comment online about things they care about very deeply is wanting a fantasy world that has no chance of coming back into being.

Is it possible for leaders and people in public life to do well when the whole internet seems bedeviled with naughty people who will retweet and repost every last mistake that people make?

I think it is possible, but trying to stand above the fray and condemning people for writing about things you’ve said is hardly going to work nowadays.

The Archbishop’s complaint about social media came just after someone published a blog post which appeared to suggest that one of the Archbishop’s closest advisors had given a briefing to a group of Anglicans which suggested that Lambeth was now not trying to avoid schism in the Anglican communion but trying to manage it – the expectation being that some parts of the Church of England (the most liberal and the most conservative) would be lost but that a coherent “middle” would survive. It was a deeply shocking position to claim to be true. So shocking that I didn’t believe it at first but have since heard others who were at the briefing confirm that this stuff was indeed said and repeat also that expectation is that there would be bargaining over which buildings to give away, within 10 years.

That blog post disappeared fairly quickly but internet genies don’t jump back into bottles and the story was out there and really rather embarrassing to all concerned.

No wonder the Archbishop posted something indicating his discomfort about social media.

But the real question is whether the social media phenomenon is the problem or whether the archbishop’s problems lie with with the things that social media point towards.

It must be terribly frustrating to have people pick up on your every utterance and make a big deal out of it.

The trouble is, in public life, the words you say have a lot of power. Social media posts rebalance that power a little and we should be welcoming the fact that we are a community that cares enough to talk about things rather than trying to remake the Anglican world into one in which bishops speak and everyone else listens uncritically.

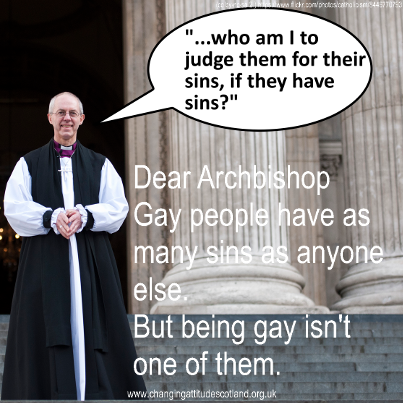

I’ve no doubt that the Archbishop will be embarrassed by posts such as this one which highlight something he said this week. Asked about the usual topic – those pesky gays, a topic that he will be asked about in every interview he ever gives, he is reported to have said:

I’m listening very, very closely to try to discern what the spirit of God is trying to tell us.

I see my own selfishness and weakness and think who am I judge them for their sins, if they have sins.

You can almost hear him dithering over the comma in that last sentence and wondering how this might sound on social media and adding a bit of theological nonsense.

Of course gay people have sins. However if the first response you make when people ask you about gay people is to talk about sin, then you are going to sound pretty homophobic. And it doesn’t matter whether you like it or you don’t like it, people are going to call attention to it online.

But is that to be too critical? What strategies could the Archbishop adopt that would help when he is asked about the Usual Topic?

The most basic thing is to recognise that everything is a conversation these days.

In fact the Archbishop did quite well in answering a question from a young Muslim who wanted to know whether he would try to convert him to Christianity.

I am not going to put pressure on you, and I wouldn’t expect you to put pressure on me.

He could have done far worse with that question than he did.

Unfortunately, he answered the question on the Usual Topic by immediately talking about sin and then parroting the “sex outside marriage in the C of E is against the rules” line.

It is a conversation, Archbishop.

That means we want to talk about it, not be told what the rules are before the conversation gets going.

It means we want to talk about it, not be told to lay off social media because it gives you the hump.

It means you can have your say so too and people will listen respectfully and carefully to what you say, but only so long as you engage with people.

It is a conversation, Archbishop. Everything is a conversation.

When the first thing you say about gay people is about sin then you can’t expect the conversation to go well.

It wasn’t helped that the second thing you said was along the lines of “some of my best friends are gay you know?”

“Marriage is between one man and one woman for life and sexual activity should be confined to marriage, that’s in the Church of England’s laws” he said. “I’m equally aware I have a lot of gay friends and I know gay clergy and they are doing incredible work.”

You say that stuff and you are going to get people observing that there’s a lot more archbishops who claim that gay people are their friends than gay people who claim archbishops are their friends.

This could be going better. It could be going much better.

And it is going to happen again. That question is going to be asked again and again and again.

There are people out there who can help you find better answers.

Guess where they are, Archbishop?

Yes – all over social media.

Recent Comments